Koira Therapy Bites

Writings on Therapy, Psychology, and other stuff

Origins of Therapy

-

Shoma Morita

Shoma Morita and Morita Therapy

-

Harry Stack Sullivan

Harry Stack Sullivan and Interpersonal Psychiatry, where there is a focus on relationships and connection.

-

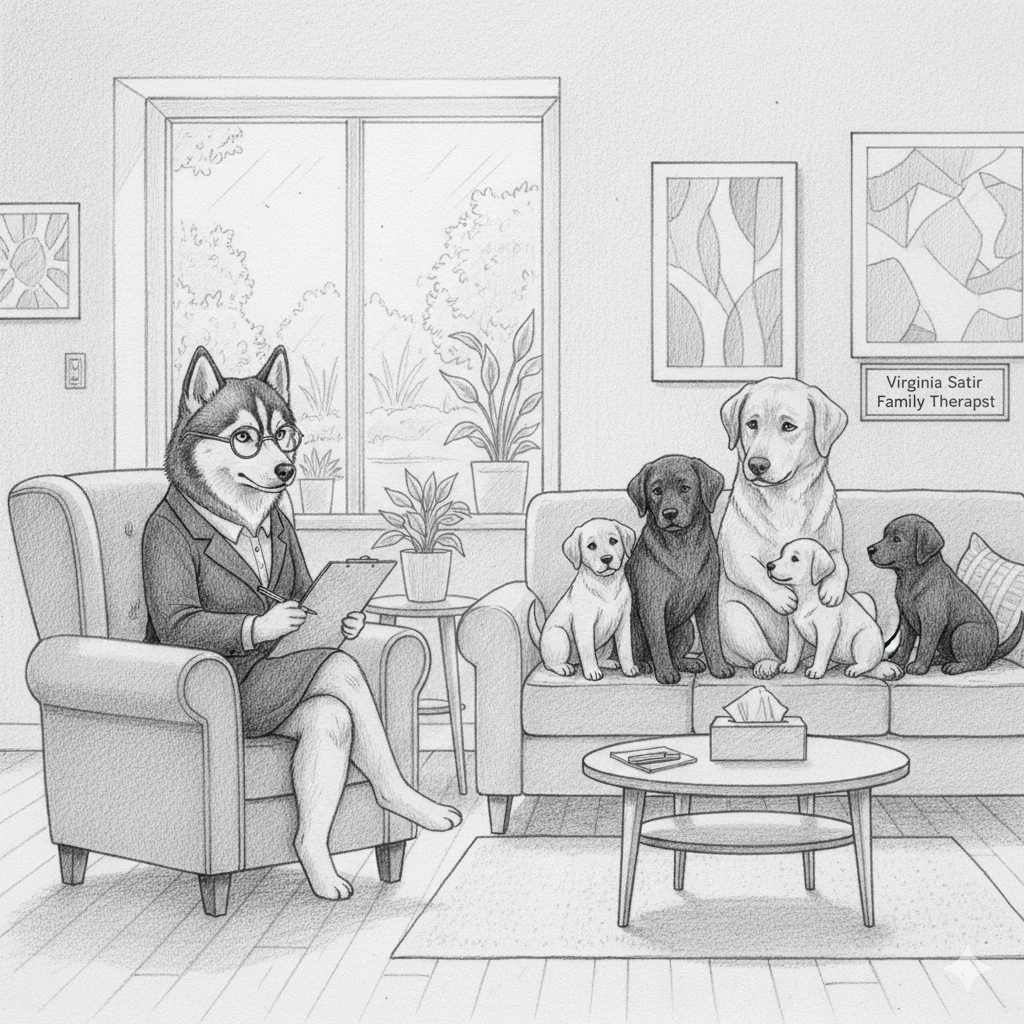

Virginia Satir

Virginia Satir and her approach to Families in Crisis

-

D.W. Winnicott

D.W. Winnicott on emotional development

-

Karen Horney

Karen Horney

-

Rudolf Dreikurs

Rudolf Dreikurs and his Adlerian approach to children and parenting

-

Alfred Adler

Alfred Adler and Adlerian Psychology.

-

Irvin Yalom

Existential Psychotherapist and Author

INSIGHTS

-

The Attention Crisis

Is Our Modern Lifestyle Generating Acquired "ADHD-Like" traits?

-

Understanding Dyslexia

A Journey of Challenges and Strengths

-

Compartmentalising for Balance

How to Navigating Life's Storms

-

The Divided Self

What Split-Brain Patients Reveal About Us

-

Antifragility and Psychotherapy

Death Anxiety, Antifragility & Psychology

-

The Fluid Self

Antonio Damasio and Bruce Hood on Self and Identity

The Attention Crisis

In our clinical work today, we are observing a curious and pervasive trend, a collapse of our client’s ability to concentrate and sustain focus, that mimics the classic symptoms of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. The question for a clinician today is this: Are we witnessing a genuine epidemiological rise in a neurodevelopmental disorder, or a neurological casualty of our hyper-stimulated culture?

The argument for the latter possibility is strong.

Is Our Modern Lifestyle Generating Acquired "ADHD-Like" traits?

The contemporary Western experience, characterized by constant digital connection and hyper-productivity, has generated a severe crisis of attention. As explored by Johann Hari in Stolen Focus, this phenomenon is increasingly being viewed through a diagnostic lens, raising a critical question for psychiatry and psychology: Is the modern environment inducing widespread, functionally impairing "ADHD-like" symptoms in the general population?

The clinical perspective suggests that the dramatic rise in reported attentional deficits may reflect an environmental mismatch, where powerful external forces disrupt the neurobiological systems that govern our focus, rather than a proportional increase in the genetically based disorder of ADHD itself.

External Pathogens: The Assault on Sustained Attention

Hari's analysis identifies systemic stressors that act as "attentional pathogens," creating the symptoms that mimic genuine inattention:

Surveillance Capitalism and Operant Conditioning: Social media and apps are engineered using principles of behavioural science to maximize user engagement. This architecture exploits our neural reward pathways, conditioning the brain to seek frequent, unpredictable bursts of stimulation (e.g. notifications and likes). Clinically, this fosters a state of fragmented attention and reinforces a habit of rapid task-switching, making it increasingly difficult to sustain effort on cognitively demanding, long-term goals.

Chronic Cognitive Load and Executive Dysfunction: The culture of "multitasking"—which is, in reality, rapid task-switching—imposes a significant "switching cost" on the brain. This continuous demand taxes the prefrontal cortex, leading to chronic cognitive exhaustion and impaired executive function (e.g. working memory, inhibition, planning). Our clients describe this as feeling perpetually "scattered," irritable, unfocused, disorganised, and unable to complete complex tasks. This presentation can be difficult to distinguish from genuine ADHD inattention.

The Neurobiology of Stress and Sleep Deprivation: The modern pressure for ceaseless productivity directly compromises the foundational requirements for healthy neural function: sleep and emotional regulation. Chronic stress triggers a state of hypervigilance, diverting cognitive resources from deep focus and thinking toward threat detection. Simultaneously, widespread sleep deprivation degrades the brain's ability to consolidate memory and regulate mood, further contributing to poor concentration.

The Critique of Diagnosis: Suzanne O'Sullivan's Perspective

Neurologist Dr. Suzanne O'Sullivan, in her book The Age of Diagnosis, provides a critical framework that supports and amplifies the concerns raised by Hari. O'Sullivan argues that our societal "obsession with diagnosis" can often be more harmful than helpful, leading to the medicalisation of normal human difference and suffering.

Her perspective on the rising tide of ADHD diagnoses is central to her critique of "diagnosis creep":

Pathologizing Normal Variance: O'Sullivan suggests that the criteria for conditions like ADHD have broadened over time, effectively drawing ordinary human experiences—such as feeling "fidgety," struggling with procrastination, or being easily distracted—into the category of a psychological disorder. She notes that the increase in diagnoses may not reflect people getting sicker, but rather "attributing more to sickness."

The Power of the Label (and the Nocebo Effect): For O'Sullivan, a diagnosis is not just an inert label; it can become a powerful narrative that we can overidentify with. While a diagnosis can provide access to valuable support, it also carries the risk of the "nocebo effect," where the individual begins to interpret every symptom or struggle through the lens of their disorder. O’Sullivan observes that a diagnostic label such as ADHD can become central to a person's identity, sometimes resulting in a "worrying gap between the perceived benefit of being diagnosed and any actual improvements in quality of life," particularly in milder cases.

The Absence of a Definitive Biomarker: O'Sullivan also points out that despite decades of research, no definitive biological biomarker exists to distinguish the behaviours exhibited by many individuals with an ADHD diagnosis from other disorders or from the spectrum of normal human experience. This reliance on subjective behavioural checklists can lead to the ADHD diagnosis being given to individuals mostly affected by environmental and cultural influences.

The combined perspectives of Hari and O'Sullivan suggest that the dramatic rise in attention concerns might be a societal problem being managed with individual psychological diagnostic labels. To address this requires moving beyond simply diagnosing and labelling, and advocating for systemic changes that restore the environmental conditions necessary for each child and teenager to develop healthy levels of attention and focus.

Understanding Dyslexia: A Journey of Challenges and Strengths

As a psychologist, I often encounter clients young and old grappling with the complexities of dyslexia. It’s important for these clients to understand that dyslexia isn't a measure of real intelligence; rather, it’s a neurodevelopmental difference that primarily affects the ability to learn to read and spell, despite conventional teaching, adequate intelligence, and sociocultural opportunity. It’s rooted in the neurological wiring of the brain, and has nothing to do with being lazy or stupid.

The School Experience: More Than Just Reading

For young people, the school environment can present significant hurdles. When a student struggles with reading fluency and accuracy, it impacts nearly every subject they study, from language, arts, and history, to mathematics, and science.

Academic Stress: Constant difficulty with core tasks can lead to intense academic stress and anxiety. Students may spend hours on homework that their peers complete quickly, leading to fatigue and a loss of extracurricular time.

Avoidance and Disengagement: To cope with repeated failure or embarrassment, some students may resort to avoidance strategies, such as acting out or withdrawing, which can mask the underlying difficulty. This can lead to them being mislabeled as "lazy" or "unmotivated," further damaging their self-esteem.

Impact on Comprehension: While many dyslexic students are excellent thinkers and listeners, the energy required to decode text can reduce the cognitive resources available for comprehension. This means they may read the words but miss the deeper meaning, hindering their ability to demonstrate their true knowledge.

The Silent Burden of Shame and Secrecy

Beyond the academic struggles, dyslexia typically carries an emotional and social burden rooted in shame and secrecy. For many, the disorder is viewed not as a neurological difference, but as a personal failure or a sign of being "less than."

Internalized Stigma: When a child's struggles are visible—in stumbling when reading aloud or producing illegible or misspelled work, they often internalize the idea that they are "stupid." This feeling is compounded by a school system that heavily values literacy as the primary measure of intelligence.

The Masking Effect: To survive socially, many dyslexic individuals become masters of masking and secrecy. They may refuse to participate in activities that require reading or writing, develop elaborate excuses, or even become disruptive to deflect attention from their inability to perform a task. This lifelong secrecy is emotionally exhausting.

A Lifelong Impact: This habit of hiding one's difficulties does not end with leaving school. Adults with dyslexia will avoid jobs that require extensive reading or writing, turn down promotions, or refuse to fill out forms in public, all to prevent their "secret" from being discovered. This self-imposed limitation can severely restrict career potential, social interactions, and even intimate relationships, perpetuating feelings of inadequacy and low self-worth long into adulthood.

The Developing Self: Navigating Identity

The challenges in the classroom ripple profoundly into a young person’s development of self-concept and identity.

Self-Esteem and Competence

School is a place where young people gauge their early competence in life. Consistent difficulty with reading and writing can lead to developing negative internal narratives, and patterns of maladaptive thinking such as “learned helplessness.”

Emotional and Social Development

The emotional reponse can manifest as frustration, shame, or anger. Socially, there can be a fear of reading aloud or having written work scrutinized, potentially leading to social isolation or reluctance to participate in group activities involving text. However, many dyslexic students often develop exceptional strengths in other areas. They can develop strong skills in problem solving, creativity, oral communication and public speaking, and design and engineering.

Jackie Stewart and the shame of Dyslexia

The life of racecar driver and businessman Jackie Stewart serves as a well known example of the negative impact of undiagnosed dyslexia and the positive development of strengths through adaptation.

Stewart struggled in school, feeling "stupid" and "thick" because of his inability to read and write easily. His dyslexia was not officially diagnosed until he was in his 40s. He left school at a young age with no qualifications, believing he was academically inept. This struggle greatly impacted his self-worth during his formative years and led to years of hiding his difficulties, a painful experience he has spoken openly about in his later years. When recalling an incident at nine years of age when asked to read in class, Stwart recalls, “I cannot exaggerate the pain and humiliation I felt that day. This pitiless torture was repeated every time I had to read in front of a class. I couldn’t do it and I didn’t understand why. Everyone was saying I was dumb, stupid and thick, and in the absence of another explanation, I started to believe they must be right.”

Stewart believes his success in motor racing was a direct result of utilising the very strengths that often accompany dyslexia: exceptional spatial awareness, rapid processing of dynamic visual information, strong hand-eye coordination, and superb mechanical intuition. These were skills that the traditional academic environment of his time failed to measure or value. He also stated that his difficulties made him more determined to succeed in whatever work he pursued. However, Stewart also paid a heavy emotional toll, even as a young adult before his diagnosis, constantly in fear that his dyslexia would be exposed and he would be publicly shamed.

There is a critical need for early identification, appropriate educational support, and a shift in perspective with Dyslexia. It is not just a deficit to be overcome, but also a difference to be understood and accommodated so that young people can develop positive self-acceptance, and be free from the isolating burden of shame and secrecy.

Antifragility and Psychotherapy

Death Anxiety and Antifragility

The application of antifragility to death anxiety from an existential perspective suggests a way of living that doesn't just cope with the reality of mortality, but actively gains from the confrontation with it.

The existential dread of death is a fundamental stressor. While resilience resists this stress and stays the same, and fragility breaks down, antifragility would leverage this core anxiety for greater meaning and stronger living.

Here are the key principles of antifragility, applied to death anxiety and existential themes:

1. Confront and Embrace the Stressor (Mortality)

Principle: Actively seek out and engage with stressors (volatility, uncertainty) to gain from them.

Existential Application: Instead of denying, minimizing, or distracting from the reality of death (fragility), one consciously confronts the inevitability of mortality and the "nothingness" (existential anxiety). This confrontation serves as a powerful stimulus.

Gain: The awareness of finitude becomes a profound motivator, pushing one toward a more authentic and deeply engaged life, rather than one lived in "bad faith" (self-deception).

2. The Upside of Finitude (Optionality/Asymmetry)

Principle: Position yourself to have limited downside risk but disproportionate upside gain (asymmetry/optionality).

Existential Application: The "downside" is a life lived in fear, resulting in Existential Guilt (the regret of not having lived fully or realized one's potential). The "upside" is Meaning and Purpose. By accepting the boundary of death, you make the finite time you have more valuable and urgent.

Gain: The knowledge that life is short makes the choice to live meaningfully a high-leverage move. It creates a "barbell" strategy: a stable acceptance of the inevitable (the safe side) paired with radical commitment to life, passion, and unique creation (the speculative, high-reward side).

3. Seek Small, Controlled Failures (Experimentation)

Principle: Take many small risks and learn from the failures, avoiding single catastrophic risks.

Existential Application: This relates to responsibility and freedom. An antifragile life involves taking many small, reversible risks in the pursuit of an authentic self (e.g., trying a new path, expressing a deeply held belief, pursuing a difficult goal). Fear of death can lead to avoiding all risk, paralyzing the self.

Gain: Each "failure" (a poor choice, a misstep, a painful experience) is quickly processed as feedback, refining one's values and actions. This rapid tinkering builds a sense of agency and Will that is strengthened by disorder, rather than being broken by the fear of making a wrong choice.

4. Via Negativa (Focus on Avoiding Fragility)

Principle: Focus more on removing sources of fragility than on predicting or optimizing for success.

Existential Application: Instead of obsessing over finding the perfect meaning (a potentially paralyzing goal), focus on identifying and removing what makes your life feel hollow, inauthentic, or dependent on external, fragile things (e.g., social approval, material wealth, or rigid beliefs). This is a form of self-purification.

Gain: By shedding the "inauthentic baggage" and dependencies that create fear of loss, you are left with a simpler, more robust core self that is inherently less vulnerable to the ultimate loss (death).

In essence, an antifragile response to death anxiety is to leverage the awareness of mortality to intensify and deepen the experience of living, transforming the terror of the void into the urgency of self-creation and meaningful action.

Key Psychological Principles of Antifragility

The following principles are adapted from the work of Nassim Nicholas Taleb and applied to personal and psychological growth:

Embrace Volatility and Disorder: View stressors, mistakes, and challenges not as things to be avoided, but as necessary inputs for growth. This means being comfortable with uncertainty and the inherent unpredictability of life.

Seek Out Appropriate Risks (Tinker): Take a large number of small, non-catastrophic risks and experiments (like trying new behaviors, skills, or ideas) that have a low downside but a potentially high upside. The resulting failures provide valuable negative knowledge (what doesn't work), which is a robust way to learn.

Build in Redundancy and Layers: Avoid having a single point of failure in your psychological or life systems. For example, relying on multiple coping mechanisms instead of just one, or having diverse interests and sources of meaning so a failure in one area doesn't crush your entire sense of self.

Focus on Avoiding the Downside (Elimination): Prioritize identifying and eliminating sources of fragility in your life, such as catastrophic risks, over-optimization for the short term, or excessive reliance on external validation. The first step toward antifragility is decreasing your potential downside.

Keep Your Options Open (Optionality): Maintain flexibility and avoid over-committing too early to a path, belief, or idea. This allows you to quickly abandon strategies that fail and capitalize on opportunities that arise from disorder.

Negative Knowledge Over Positive Knowledge: Value information about what is wrong or what doesn't work (through experimentation and failure) more highly than prescriptive "positive" advice (what is right or what worked for someone else).

Antifragility and Psychology

This idea of antifragility, the notion that we don't merely survive shocks, but often gain from them is, for a psychologist, is a valuable insight. Nassim Nicholas Taleb, the man who described this phenomena in his book Antifragile, has given us a new way to look at how our clients can respond to significant stressors and trauma.

In the 1888 book of aphorisms, Twilight of the Idols, Friedrich Nietzsche wrote in original German text "Aus der Kriegsschule des Lebens. —Was mich nicht umbringt, macht mich stärker", which translates to "From the military school of life - what doesn't kill me makes me stronger". This often used quote is frequently linked to the concept of antifragility, and what is referred to as Post-Traumatic Growth.

Post-Traumatic Growth

Post-traumatic growth is the positive psychological change experienced as a result of struggling with a highly challenging or traumatic life circumstance. It is not simply a return to the baseline level of functioning, which is typically described as resilience. When we experience post-traumatic growth it is a state of functioning that is better than before the trauma occurred.

Post-traumatic growth occurs when a traumatic situation or event shatters an individual's core beliefs about themselves and the world, forcing them into a psychological struggle (often involving deep reflection or rumination) that leads to the construction of a new, more refined, and meaningful worldview.

The positive changes could include a new appreciation of life, improved relationships with others through greater intimacy and connection, an increased sense of psychological contentment and acceptance, acknowledging new possibilities in life, and a spiritual or existential change in perspective.

The Courage of Vulnerability

The clients I have worked with who see themselves as very fragile tend to spent a lifetime meticulously trying to engineer a safe and static world and existence. They have sought absolute predictability, a seamless, well-managed life where no unexpected event can pierce the illusion of permanence and safety. They resist change, avoid risks, and cling desperately to their pre-existing answers about life's meaning. When life inevitably arrives, uncontrollable and unpredictable, it finds their defences brittle and their core shattered.

The path to antifragility, paradoxically, requires embracing your vulnerability. It is found in the courage to face and walk towards life, in spite of its uncontrollable nature. For example, all of us fear death and are terrified of mortality and thus we become terrified of fully living. With an antifragile mindset, we can uses the certainty of death as a catalytic agent, a spur to live life more fully. Each moment of confrontation strengthens the resolve to live without regret. The fear of the death becomes the energy for living.

Antifragility is not achieved through an avoidance of pain, but a deliberate confrontation with it

The Therapeutic Imperative

As therapists, we are often asked to fix the broken parts of our clients, to restore the patient to their previous, supposedly healthier state. But if we truly subscribe to this notion of antifragility and post-traumatic growth, our goal would be different. We need to help our clients aim for growth, not just resilience. We also must resist the temptation to encourage the client to make safety their goal. Instead, we must help the patient become ok living in this unpredictable and uncontrollable world.

To be psychologically antifragile, then, is to possess a mindset that is ok with some turbulence and stress, because it understands that stillness and absence of stress is stagnation and decay. No human is invincable. At times we will all be a bit broken and bent out of shape. The aim is to grow for having been stressed. No life is worth living without the courage to risk a fall.

The Divided Self: What Split-Brain Patients Reveal About Us

In the study of neurology, there are cases that do more than illuminate the workings of the brain—they challenge our very notions of identity, consciousness, and what it means to be human. Among these, the study of split-brain patients stands as one of the most profound. These individuals, whose corpus callosum—the thick bundle of nerve fibres connecting the brain’s two hemispheres, has been surgically severed, offer a rare and startling insight into the architecture and workings of the human mind. The surgical procedure, known as corpus callosotomy, is typically performed to alleviate severe epilepsy. By interrupting the electrical storms that rebound between hemispheres, seizures can be dramatically reduced. However, this procedure causes some interesting changes in perception and behaviour.

Imagine a man whose left hand reaches for a shirt while his right hand pushes it away. Or a woman who giggles at a provocative image shown to her left visual field yet cannot explain why. These are real accounts from the pioneering research of Roger Sperry and Michael Gazzaniga in the 1960s. Their experiments revealed that when the corpus callosum is severed, the two hemispheres of the brain, each with its own specialties and quirks, can no longer communicate directly. The result is a kind of cognitive duality: two minds, cohabiting one body.

The left hemisphere, typically dominant for language and analytical reasoning, becomes the narrator of experience. It interprets, rationalizes, and explains. The right hemisphere, often more attuned to spatial awareness, emotion, and nonverbal cues, continues to perceive and respond, but without the ability to articulate its insights. In split-brain patients, these hemispheres operate independently, each processing its own stream of information, sometimes in harmony, sometimes in conflict.

What is most remarkable, however, is not the division itself, but the seamlessness with which patients adapt. They do not feel split. They do not report a sense of duality. Their subjective experience remains unified, even as their neurological reality is divided. This suggests that our sense of self—our feeling of being one coherent person—is not a direct reflection of brain anatomy, but a narrative we construct. The brain, it seems, is not a singular organ of thought, but a federation of processes, held together by story.

Case Studies: Lives Behind the Data

To understand the implications of split-brain research, we can look at the lives behind the data. One patient studied by Michael Gazzaniga, underwent corpus callosotomy to treat severe epilepsy. In an experiment, the word CAR was flashed to his right visual field (processed by the left hemisphere), and he easily said “car.” But when PAN was shown to his left visual field (processed by the right hemisphere), Joe said he saw nothing. Yet when asked to draw with his left hand, he sketched a pan handle.

What this shows was that Joe’s right hemisphere perceived the word but couldn’t verbalize it. His left hand, controlled by the right hemisphere, could express the concept through drawing. Each hemisphere can process and respond independently, even without conscious awareness from the other.

Sperry and Gazzaniga also found that when an object was presented to the left visual field, patients could not name it but could identify it with their left hand. Conversely, objects shown to the right visual field could be named and manipulated with the right hand.

What this shows is that each hemisphere specialises in different functions: the left in language, the right in spatial and visual tasks. Without the corpus callosum intact, these functions remain intact but isolated. Patients often felt normal, despite the neurological split, suggesting that our sense of unity is a psychological construct.

What Split-Brain Patients Reveal About the Nature of Self

Perhaps the most astonishing insight from split-brain research is not the division of function, but the unity of identity. These patients, despite having two hemispheres that no longer communicate directly, do not feel fractured. They continue to experience themselves as one coherent person.

This challenges the intuitive belief that what we perceive as our ‘self’ is singular and indivisible. Instead, it suggests that the self is a construction—a narrative woven from multiple threads of perception, memory, emotion, and intention. The brain, it turns out, is not a singular organ of thought, but a dynamic system of specialised modules. And the sense of “I” emerges not from any one part, but from the interplay between them.

In split-brain patients, we see that each hemisphere can operate independently, even forming distinct preferences, reactions, and interpretations. One hemisphere may laugh at a joke the other cannot explain. One hand may reach for an object the other ignores. And yet, the person remains whole, not because the brain is unified, but because the mind is adaptive.

This teaches us something profound: that unity is not anatomical, it is experiential. The self is not a fixed entity, but a fluid process. It is not a solitary voice, but a chorus. And in moments of disconnection, the mind tries to unite as it compensates, adapts, and continues to build and narrate a coherent story.

Split-brain patients remind us that our sense of self is not a mirror of the brain’s structure, but a triumph of its function. They show us that identity is not given, it is made. And in that making, we find the essence of what it means to be human.

The Fluid Self: Antonio Damasio and Bruce Hood on Self and Identity

In clinical practice, we often speak of the self as if it were a stable construct, this one thing we can assess, support, or restore. But the reality is far more complicated and nuanced. The self it seems is not a fixed entity. It is dynamic, layered, and deeply contextual. Antonio Damasio and Bruce Hood, from their respective perspectives in neuroscience and psychology, offer compelling frameworks for understanding the self, ones that resonate with clinical observation and therapeutic insight.

Damasio and the Embodied Self

Damasio proposes that the self is not housed in a single brain region, nor is it reducible to just memory or cognition. Rather, it emerges from the ongoing interaction between the brain, the body, and the environment. He distinguishes between the “core self”, the moment-to-moment sense of being, and the “autobiographical self,” which is shaped by memory, narrative, and social experience.

This distinction is clinically significant. In cases of neurological injury, trauma, or dissociative states, we often see disruptions in autobiographical continuity. Yet patients may still retain a core sense of presence. In clinical practice we will meet individuals who have lost access to their personal histories, yet remain emotionally attuned, relationally responsive, and capable of experiencing joy, fear, and connection. Their selfhood is not erased, it is reorganised.

Damasio’s model helps us understand how identity is influenced by both physiological regulation and psychological integration.

· The core self is grounded in homeostasis, the body’s internal balance, and is expressed through feelings, sensations, and immediate awareness.

· The autobiographical self, by contrast, is constructed through reflection, language, and social feedback. It is the story we tell ourselves about who we are.

Bruce Hood and the Social Construction of Self

Psychologist Bruce Hood also challenges the notion of a unified, coherent self. In his book The Self Illusion, Hood argues that the self is not a singular entity residing in the brain, but a narrative construct and an illusion generated by the brain for functional and social purposes.

“We all certainly experience some form of self,” Hood writes, “but what we experience is a powerful depiction generated by our brains for our own benefit.”

From a developmental perspective, Hood shows how the self emerges through social interaction. Children learn to see themselves through the eyes of others. They internalise roles, expectations, and cultural narratives. The self is not discovered but it is assembled over time and through experience. And crucially, it is assembled in relationship.

This has profound implications for therapy. When clients struggle with identity, whether due to trauma, loss, or existential crisis, we are not helping them “find” a buried self. We are helping them reconstruct a coherent narrative, one that integrates past experience with present awareness and future intention. The self is not a destination; it is a process.

Hood’s view also aligns with what we observe in clinical work with dissociation, identity disturbance, and even everyday role conflict. The self is multifaceted. It shifts across contexts. And yet, we cling to the illusion of unity because it offers psychological stability. As Hood notes, “The illusion of self is not a flaw, it’s a feature.”

Integrating Two Perspectives

Together, Damasio and Hood offer a layered understanding of identity. Damasio roots the self in the body and its regulatory systems. Hood situates it in the social and cognitive architecture of the brain. One emphasizes embodiment; the other, narrative construction. Both agree: the self is not fixed, it is fluid.

This insight pushes therapists to work on multiple levels. We focus on relationships, the body, the emotions, the memories, and the stories. We can help clients regulate, reflect, re-connect, and rewrite. We recognize that the self is not a singular truth to be uncovered, but a living system to be supported.

Damasio and Hood remind us that the self is both embodied and imagined. It is both felt and narrated. And in embracing this complexity, we come closer to understanding what it means to be human—not as a fixed entity, but as a living, evolving human.

Compartmentalising for Balance: How to Navigating Life's Storms

As a clinical psychologist, I often sit with individuals who are grappling with a singular, overwhelming problem. It could be a relationship difficulty, a setback at work, a health concern, or a financial strain. While the importance of these issues are undeniable, a common and often detrimental pattern I observe is the way this one problem can overshadow everything else good in a person's life, effectively harming their emotional well-being and quality of life. When we focus all of our attention on one area of life, it can lead to a diminished connection with all other areas of our life.

The Oil Tanker Approach

Consider the engineering of an oil tanker. These colossal vessels, designed to transport vast quantities of liquid, face the constant threat of rough seas. A key feature of their resilience is the use of multiple, watertight compartments.

Why this design? When navigating waves, an oil tanker’s load, the massive volume of oil, is constantly shifting. If the ship had only one large compartment, the liquid would slosh freely from side to side. In heavy seas, this single, moving mass of liquid could generate enormous momentum, causing the ship to lose its balance rapidly, and potentially capsize. This phenomenon is called the "free surface effect."

However, with multiple compartments built in to hold the oil, the shifting oil is contained in small, independent sections. This restricts the movement of the load, helping the vessel maintain its stability and balance even when encountering turbulent waters. If one compartment is compromised, the integrity of the others remains largely intact, allowing the ship to maintain buoyancy and continue its journey.

Similarly, our lives are comprised of numerous compartments. We have our relationships with family and friends, our work, our passions, our physical health, our hobbies and interests, our spiritual practices, and our community interests. When a significant problem arises in one of these "compartments," it's natural for it to demand more of our attention and energy. The danger, just like the single-compartment ship, lies in allowing that one problem to become a single, overwhelming focus. When all our emotional energy and attention moves into that one issue, it can create emotional dysregulation, and a loss of balance and perspective, that can lead to disconnection, depression, and elevated anxiety.

The Anchor of Daily Rituals

I have experienced this problem of loss of balance many times in the past. At times the focus on the difficult aspects of my work as a psychologist became my single, all-consuming compartment. In response to this I stopped catching up with family and friends, neglected my interests outside of my work, stopped exercising, found myself feeling more anxious, and thinking the world was against me. The single "problem" in my professional life was allowed to become my sole focus, causing my perspective on life to lose its balance.

Over time I have learnt that life balance is essential. To deliberately connect with all of these healthy compartments, we need to consciously focus on all of the small things that make our life worth living each day.

These are our daily rituals that, though seemingly minor, provide structure, predictability, and moments of contentment and joy. Think of the value of a morning walk, a mindful few minutes spent savouring your first cup of coffee, or a brief chat with a neighbour. These rituals are small but important daily reminders that not everything in life is related to that one problem. They help counter the globalising effect of a major problem by reminding you that you can still experience contentment, joy, and human connection in the present moment.

The key to navigating these problems in life lies in the conscious practice of compartmentalization—refusing to let one problem area overwhelm the stability provided by the others healthy areas of your life. It is important to acknowledge the problem, addressing it as best you can, but avoid letting it diminishing your capacity to live your life.

The Roots of Our Relationship Anxiety

"To survive, animals must avoid predators; humans must avoid loss of relationships."

"Many animals live independently when only a few weeks old. We, however, cannot. Children rely on others to survive. Therefore, any feeling threatening the safety of our primary relationship endangers our survival, triggering anxiety."

Jon Frederickson

From birth, our wellbeing depends on the stability and safety of our relationships. John Bowlby, the founder of attachment theory, proposed that children are biologically wired to seek closeness to caregivers as a means of survival. When these caregivers respond consistently and warmly, the child’s nervous system learns that safety and comfort are available in times of distress. Over time, this experience forms an internal sense of security, a belief that others can be trusted, and that the self is worthy of love and care.

However, when caregivers are emotionally unavailable, unpredictable, or frightening, the child’s attachment system becomes activated but remains unresolved. As Bowlby described, this uncertainty creates chronic anxiety: the child feels compelled to seek safety from the very person who also feels unsafe. Jon Frederickson builds on this idea, observing that when our key relationships feel threatened, our body reacts as though our very survival is in danger. The anxiety we feel in these moments is not irrational, it is the echo of a nervous system that once depended completely on others for safety.

Children exposed to relationship stress develop coping strategies to manage this inner conflict. Some withdraw or avoid, hoping to stay invisible and safe. Others become angry or rebellious, using control to manage unpredictability. Still others people-please, trying to maintain harmony and prevent disconnection. In some, the mind protects itself by dissociating, numbing painful emotions to survive the moment.

While these strategies serve the child’s survival needs, they often become barriers in adult life. When we experience conflict, rejection, or intimacy, those old patterns re-emerge. We may distance ourselves, cling too tightly, or shut down emotionally—all attempts to restore a sense of safety that was once missing.

For example, consider Judith, a woman in her thirties who becomes deeply anxious whenever her partner grows quiet or seems preoccupied. Even when there’s no real conflict, she feels a rush of panic and a need to “fix” the situation. In therapy, Judith begins to see that this reaction echoes her childhood, where her mother’s silence often preceded emotional withdrawal. As a child, Judith learned to soothe her mother’s moods to feel safe. Now, as an adult, her body reacts the same way whenever emotional distance appears, interpreting it as danger rather than simply difference. Over time, therapy helps Judith recognise this automatic fear, comfort the younger part of herself that feels unsafe, and develop new ways to stay calm and connected even when others pull away.

Therapy offers us a chance to identify and transform these learned strategies. By understanding their origins and experiencing safety within a therapeutic relationship, we begin to rewire our emotional responses. As Bowlby and Frederickson both highlight, healing occurs not through avoiding anxiety, but by facing it within secure and supportive connection—learning, perhaps for the first time, that love and safety can truly coexist.