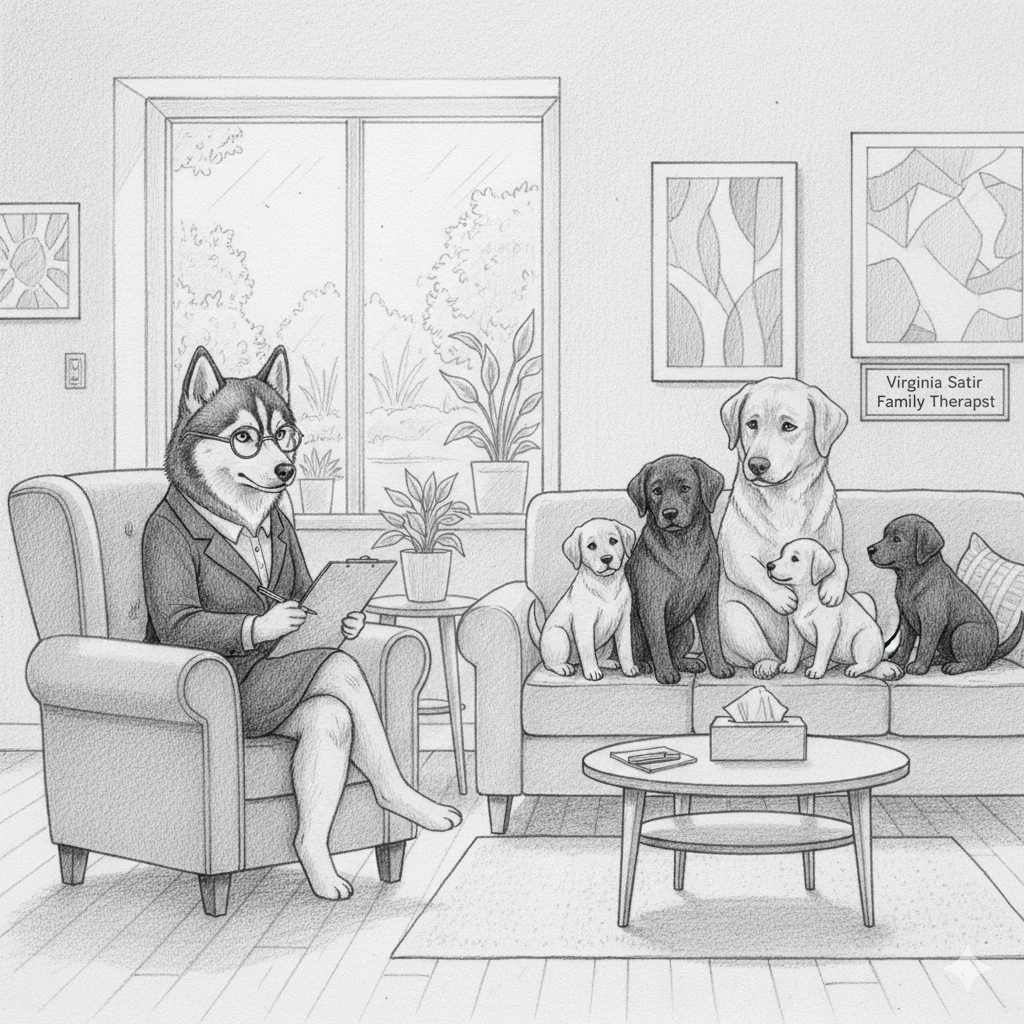

Virginia Satir

The Congruent Life: Virginia Satir, Self-Worth, and Family Therapy

The woman who made one of the biggest contributions to the practice of family therapy was not your typical academic. Virginia Satir, who began her career as a teacher and then a social worker, came to family therapy with the eye of an dramatist and the soul of a humanist. Satir was often described as warm and genuine. She saw the entire family as a living, breathing, and often profoundly broken system that could be repaired.

The Problem Is Not the Problem

Satir's core family therapy thesis was simple: the problem is not the problem; coping is the problem. Families came in with symptoms—a child's behavioral issue, a spouse's depression, but the real pathology was rooted in the desperate, dysfunctional ways they had learned to communicate and manage their own self-worth.

She could observed, with clarity, the stress-driven, incongruent communication stances that family members would deploy like emotional shields:

Placating (agreeing with everyone, apologizing constantly)

Blaming (accusing others, masking their own vulnerability)

Computing (being hyper-rational and emotionally detached)

Distracting (changing the subject, acting irrelevant)

None of these stances allowed the individual to be fully present with the family; they were all strategies to survive a perceived threat to one's self-esteem. The therapeutic goal, therefore, was not merely to fix a symptom, but to usher the family toward Congruence, a state where an individual’s internal experience (feelings and thoughts) aligns transparently with their external expression (words and body language). This was her bedrock of emotional health, a state of authentic being where one can say, "I mean what I say, and I own what I feel."

The Centrality of Empathy and Self-Worth

In the Satir model of family therapy, self-worth is a necessity. To feel and express authentic emotion, a person must first possess a foundational sense of self-worth. Satir contended that low self-esteem was the root cause of relational distress, driving individuals to use those defensive communication stances to protect their fragile inner sense of value.

Satir believed that if people truly understood and validated their own worth, they would naturally begin to relate to others with openness, honesty, and empathy.

The Development of the Fully Human

Satir’s understanding of human development was optimistic and growth-focused. She believed that everyone carried the innate resources required for positive change. People were not broken things to be fixed, but rather dynamic entities who had simply gotten stuck in coping patterns learned in their original family unit (family of origin).

Satir saw the mother-father-child triad as the starting point for all future relational learning, the place where one first learns to connect, to communicate needs, and to manage differences. In therapy, Satir guided adults to re-experience and re-frame their past hurts of their own childhood. Her goal was to resolve the past's contamination of the present and break the cycle of dysfunction by unlocking new options in relating to the other family members.